Tag: Hello World

All blog posts-

Season 6 of the Hello World podcast is here

Our first episode asks: Do kids still need to learn to code?

-

Hello World #23 out now: Global exchange of computing education ideas

Stories and research on computing education from over 20 countries

-

AI isn’t just robots: How to talk to young children about AI

Help your kids understand AI tools and their limits

-

Hello World #22 out now: Teaching & AI

A snapshot of the current landscape of AI education

-

Introducing the Hello World newsletter

News from Hello World and the Foundation in your inbox every month

-

Hello World #21 out now: Focus on primary computing education

Inspiration and ideas for computing education in primary school

-

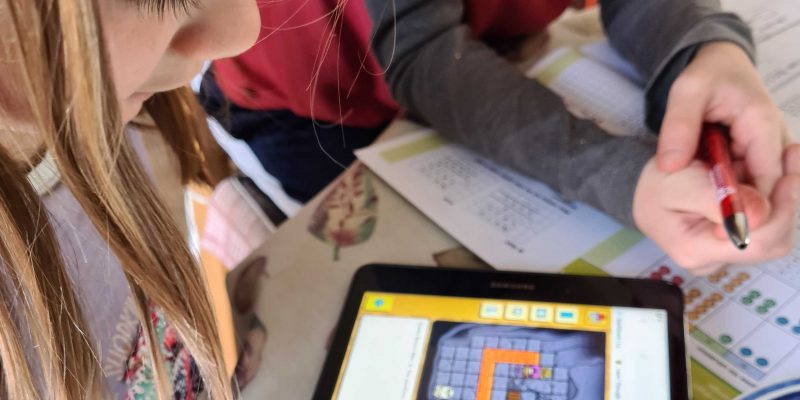

Preparing young children for a digital world | Hello World #21

It’s about children's right to be active citizens in the digital world

-

Computing curriculum fundamentals | Hello World #20

Computing systems need to be at the heart of computing curriculum design

-

Reflecting on what we teach in computing education and how we teach it

Our special editions of Hello World help you reflect on your teaching

-

Out now: Hello World’s special edition on Computing content

A Hello World special issue about what we teach in the Computing classroom

-

A taxonomy of Computing content for education

Describing the diverse range of concepts and skills that comprise Computing

-

Back to school 2022: Our support for teachers

See the breadth and depth of teacher support we offer you